How to Return to a Place that Isn’t There : Group Show

Past exhibition

Overview

Cómo volver a un lugar que no existe

Carla G. Colomé

My friend Haydée has asked me to write. She almost never asks for anything. She almost always gives instead. In my case: clothes, food, her bed, her time. I say yes. I couldn't answer her any other way. It is her latest exhibition as curator at Thomas Nickles Project, a small Lower East Side gallery that for four years has hosted her and several contemporary Cuban artists. Haydée loves it when I tell her that at six o'clock in the evening, just about the time the gallery’s doors close, I'll pick her up to go to a Chinese restaurant whose name we can never remember, but which is our favorite in the whole city. She says that when I say that I will pick her up after work, what she really feels is as if someone, let's say her mom, is picking her up after school. Haydée is from Bahía Honda, a Cuban village, coastal and western, a fishing village that only has a polyclinic, a school, a rehabilitation room, and a house of culture. I am also from a town with a store, a statue, a discotheque, and an arcade. We know where we come from, and there is nothing we like more.

I met her in the Havana of our twenties. Then we met again, almost a decade later, in New York City, the most Havana-like place there is, and the most different too. More than once I've walked alone on Riverside Drive feeling like I'm actually walking along Havana Bay. Long ago we began to inhabit the place of memories through the spaces of the present. I don't know why, or what for, Haydée asked me one day to answer a question: “Do you have a memory of something that your parents, grandparents or neighborhood friends taught you when you were growing up that you thought was true for a long time, but wasn't?” As an example, she then told me that since she was born in the nineties, just like me, all the facades of the houses in town were painted white lime with brush hairs stuck to the walls, something that particularly caught her attention. Her parents told her it was crab hairs. Then Haydee said, “It's something I believe to this day, even if it's not true.”

My memory, like almost all of my childhood memories, was related to my dad. I told her that for a long time my father would stretch his feet and move his knees, and then he would tell me that instead of having a knee, what he had was a mango seed. When I would ask my dad how it could be a mango seed, he would say yes, that when he had his surgery there were no knees in the hospital and so the doctors decided that what he should have as a replacement was a mango seed. We had been in an accident when I was very young, an accident where my mother died and my father took over, so every single memory I have only includes him. And so, I didn't think the story of his knees was so far-fetched. I always believed him to have a mango seed in his body, I also choose to believe him to this day. It is my way of remembering who we were. Sometimes I lie in bed and travel back to the time when we would both ride our bikes along the town's boardwalk and my dad would ask me to look at how blue the sea was. I still seem to feel his whistles at the end of elementary school, which I would hear everywhere, and that was enough for me to drop everything and run hard into my dad's arms. Sometimes I brush my hair, and I think of the braids he learned to weave for me. They were thick, deformed, but I worshiped them. Or the blackout nights lying in the doorway of the house, when I would ask him questions like: What was my mother like? How did she have her toenails and fingernails?

I could say that my dad is the person I love most in life, but that doesn't explain who my dad is. Sometimes I want to catch myself and take myself back to a time when I was nine, ten, eleven years old. A time when only he and I existed in the neighborhood, a neighborhood full of kids climbing trees, scaling on rooftops, paddling down the river, exploring the underground shelters the Cuban military made in case the war came, as we were promised it surely would someday. Even when I saw a plane crossing the sky, and I thought it was definitely the Americans, and with the Americans, the war, I would run to wherever my dad was, because there was no way I was going to die without being by his side. Sometimes, in a fit of selfishness, I have silently asked to die before him, then prayed that it would never be so. He doesn't deserve such great pain.

Today my father lives in a small efficiency, somewhere far away from Miami, where he arrived a few years ago after never wanting to leave Cuba, but after I left, and the people of the neighborhood left, and our town was practically empty, with the store almost empty, the discotheque empty, the arcade empty, he left too. There remains, still, the statue of a bronze corroded by time, so corroded that at any moment it could collapse. Sometimes I call my dad, and I don't have much to say to him. Sometimes the calls last a minute. Sometimes two. We talk about the same thing. How his job as a gardener went, how my job as a journalist went. What he ate, what I ate. If he's already going to sleep, if I go to bed earlier. I call him on his new phone number with pain and sometimes even guilt: he is far from home, from the yard that was once full of dogs, ducks, pigeons, rabbits and pheasants. From the town on the coast, wide and inhabited by the most mysterious shapes the sea has.

We're in the same country now, and we've probably never been further apart. I know he knows; he knows I know. Very regularly I stop by to see him, looking for something that was—my father who makes jokes, who teases, who whistles, who makes batches of meals for all my hungry friends. But he's gone. He's an aging, sad, lonely, quiet, diminished dad, pruning not the plants in his yard, but those of a wealthy Miami family. We don't know how to do it differently. Some things make sense only in certain places. My dad is my dad wherever, but only he and I know what it means to be him and me in our house in Baracoa Beach. I don't tell him, but I want to hug him and go back to the time together when I was nine, ten, eleven years old. It's not going to happen. No one has found a way to go back to a place that doesn't exist.

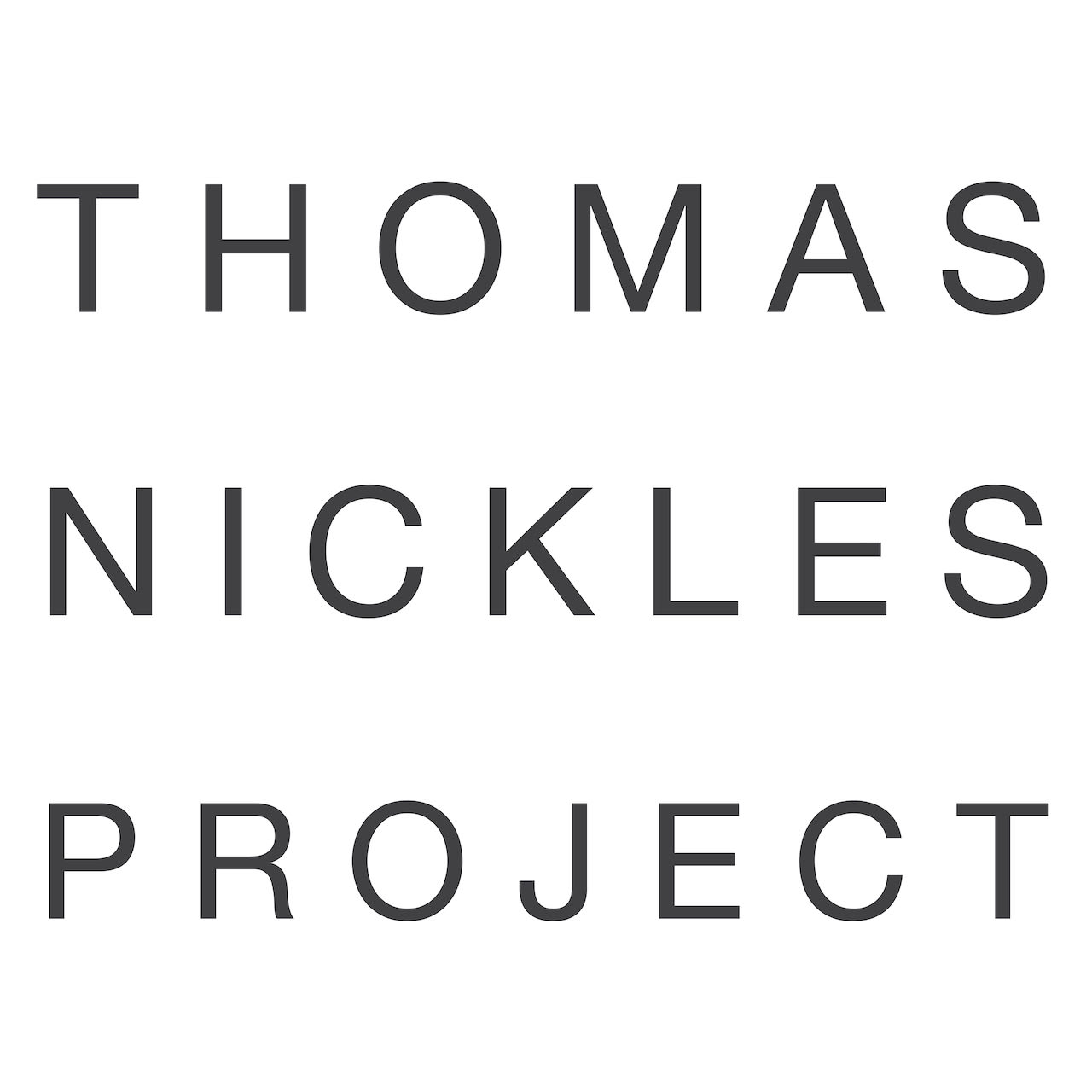

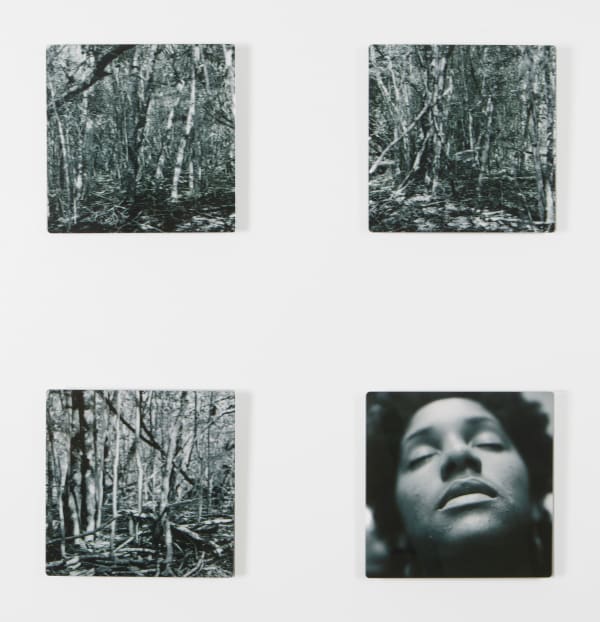

Selected Works

Installation Views