An Inventory of Tools for Coping: Elsa Mora

-How do you define yourself and your work and why?

As an artist, I find it hard to define myself and what I do. Perhaps it’s fear of closing the door to possibility and re-invention. Like every other human, I am in constant conflict with myself, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. There is no life without tension and friction, and the need to keep moving towards something else. With that said, a lot of what I do in my art practice is observation-based and process-oriented. Art is my comfort zone and the place where I can be most vulnerable and honest.

-How has your practice changed over time?

My practice per se hasn’t changed that much, the core has always been curiosity and experimentation. What has changed is the way I understand myself and others and the materials I have explored for years. The more I learn about all these things, the more confident and freer I feel to go deeper into the search.

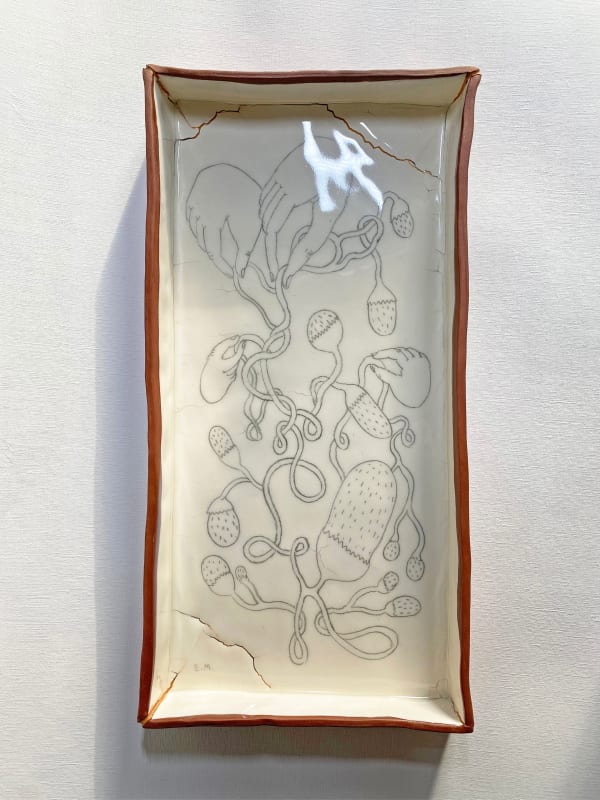

-You work in a variety of medium, what prompted you to shift to ceramics for your latest series and why the mix of porcelain and clay?

I don’t think I can be married to a single media, working with a variety of materials gives me the freedom to express myself better. Every media has its own language and I enjoy exploring and sometimes combining them. The reason I started making ceramics this year was Lisa Naples Clay Studio in Frenchtown, NJ, located across the street from where I live now. I always wanted to get back to ceramics but never had the ideal conditions for it. Having the studio across the street was an invitation to reconnect with clay. Lisa Naples has a beautiful red clay formulated specially for the studio that I love, that’s how it all started. Then I was missing porcelain, which was the first type of clay that I used in the past to produce a large body of work, so I got 50 pounds of it. There are many types of clay available out there, but for now I’m happy with the two I’m using, they have very different personalities, but complement each other well.

-There is a wonderful playfulness to your ceramics. Where does this originate? What are some of your influences?

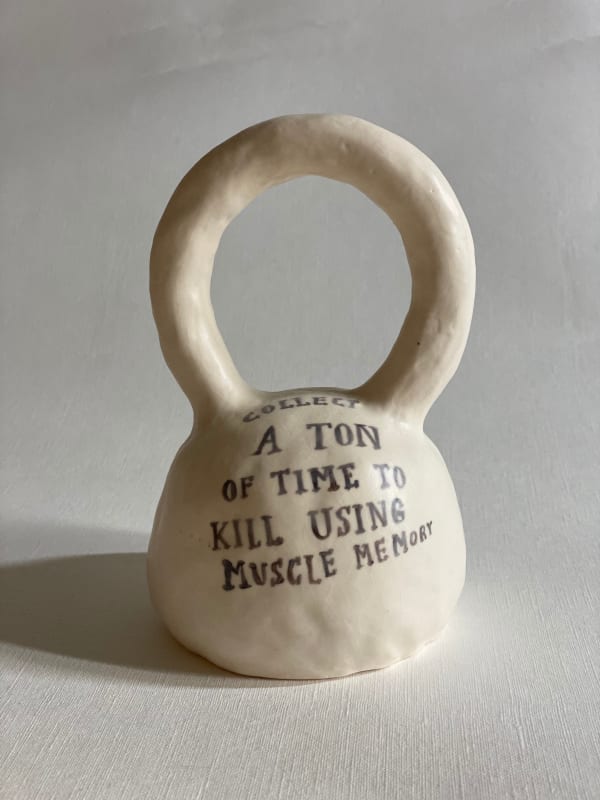

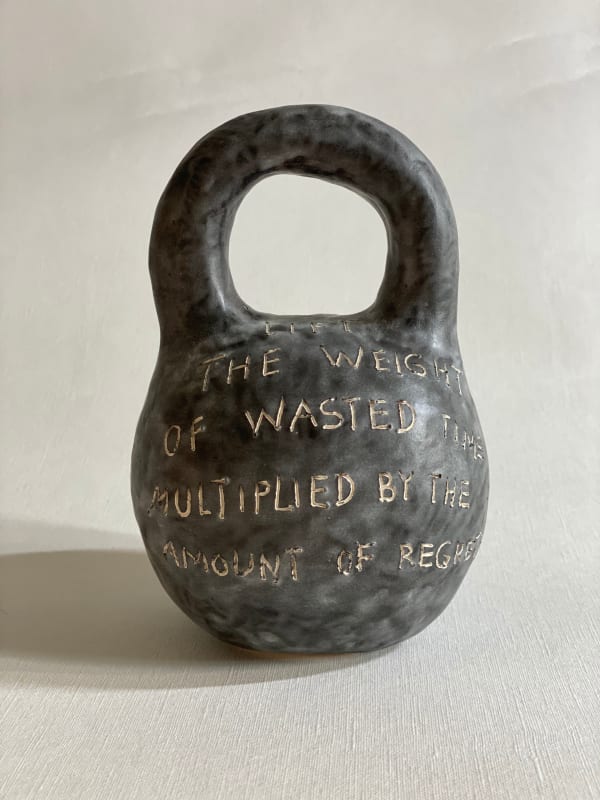

The playfulness of these ceramics is a visual impression that I use to catch the eye’s attention, but underneath the surface there are difficult subjects, similar to One Hundred and One Notions, a collection of 101 small sculptures that I made with paper and glue for my previous solo exhibition, Paper Weight. Each of those sculptures represents a mental condition. In the case of these small ceramics, I’m using them to explore the subject of coping and survival tools during times of crisis.

-Can you describe the process of making each of the series from start to finish?

Ceramics:

These ceramics start with a mental idea of what I want. Some of them represent identifiable objects, while others are abstract and suggestive of organic shapes found in nature but all of them are connected to the subject of coping. It is mostly through the titles what I reveal some aspects of the ideas that I’m exploring. In terms of fabrication, I use slabs that I create by pressing pieces of clay on a table surface with a wooden rolling pin. I then cut out different shapes with a potter’s knife to combine and create these objects. What follows is the application of colored underglaze with a brush, followed by a period where I let the pieces dry until they’re ready for bisque firing. Once the piece is in the bisque state, I sometimes draw on the surface with underglaze pencils. The last step consists of applying glossy or satin glaze on the surface and proceeding with the final firing.

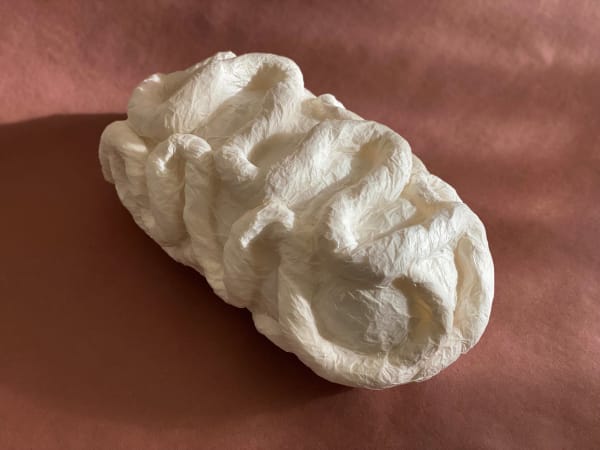

Paper pieces:

I wanted to include works made with paper in the show because of their repetitive nature. They are a form of meditation for me. I created these pieces by cutting small teardrop shapes with very sharp scissors using translucent paper. Then I glued each teardrop on a black paper surface forming random and interesting patterns. These patterns are a reference to how the mind works sometimes by moving from thought to thought into deep rabbit holes that take us far away from where we started.

There are also paper sculptures that have a connection to the ceramics formally and thematically.

Paintings:

The exhibition includes some acrylic paintings on wood that I was excited to create in between making the ceramics and paper works. They’re mostly abstract-looking and are visual maps of unresolved conflicts. I painted them with brushes but also with my own hands and fingers.

-There is work from several series that has come together in An Inventory of Tools for Coping. Can you talk a little about how these works function as tools and how the different series inform each other?

It was important for me to make an “inventory” of the things that I have done in the last few years to cope with crisis that my family has gone through. Each of the series touches a different aspect of this process. The works are all in function of the same pursuit, which is processing trauma to find resolution and closure, while expanding the capacity to overcome obstacles in creative ways.

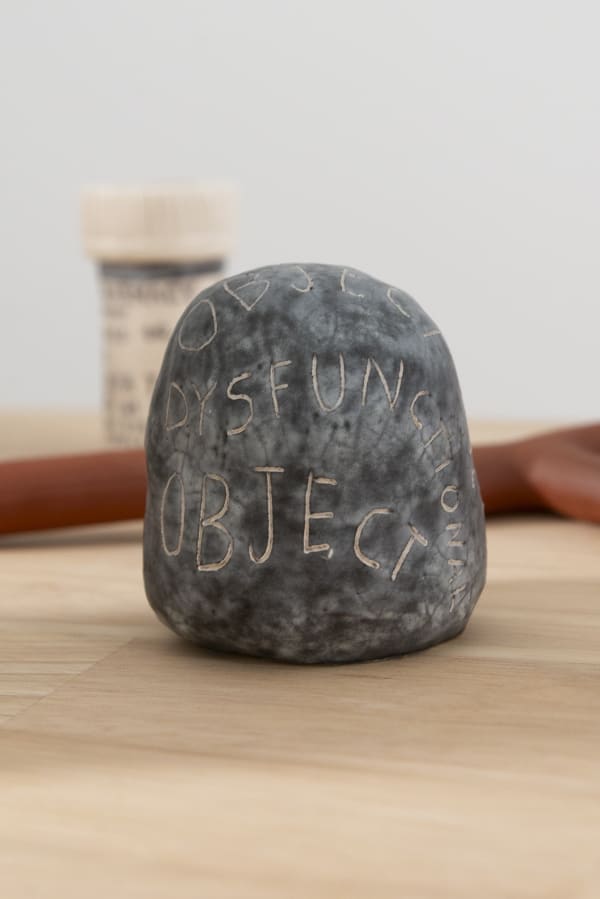

-I’m curious about the difference between a functional and dysfunctional object. Can you expand on this?

Some neurotypical people describe neurodiverse individuals who struggle as “low functioning.” It all started with this observation. I believe that the sole purpose of a person is not necessarily to be able to do what most people do or to produce something functional or tangible for others. There are many ways to be human and bring value into our shared space. I wanted to expand on that idea by exploring objects and their level of functionality. Some objects have a functional use such as a cup for drinking liquids or a hammer for making furniture, while others are not “functional,” such an art object. Regardless of their functions, they can both be equally appreciated and celebrated. This is an idea that I want to keep exploring.

-What has been the role that notions of mental and emotional health have played in your practice in recent years?

Mental and emotional health have played a crucial role in my practice, especially in the last few years. My son’s journey through autism, (he recently turned 18), has been full of lessons, surprises, struggles, celebration, sadness, and discovery. My art practice has kept me moving, activated, and optimistic. I have learned not to try to erase sadness, but rather to understand its language and potential to reveal important truths. As a caregiver and artist, I have learned that sometimes turning emotions and situations into fuel for creativity is the best medicine.

-Is the transformation, represented in your autobiographical and deeply personal work shown in this exhibition, primarily related to a visual motif or to an emotional state?

This work is a mix of both elements. The visual motifs are a way to get to the emotional part and vice versa. They’re holding hands and supporting each other.

-Do you find ways to return to Cuba, within your practice?

Cuba is in me wherever I go. All the memories and experiences I had while growing up there influence everything I do now even if I don’t want to admit it. Some of my Cuban experiences were traumatic and some were defining. Cuba is a complex subject full of contradictions, strong emotions, and explosive energy. Put three Cubans together and you will get a party, a fight, and a funeral, all three for the price of one. I’m kidding, but the truth is that there is something intense about being Cuban, and I don’t complain about it, that has probably made us good survivors.

-Do you think art can be a coping mechanism?

Absolutely. It’s probably the best coping tool for anyone who has tried everything else already unsuccessfully. I highly recommend it.