Ain't No Cure: Group Show

Sometimes I wonder what I'm gonna do, 'cause there ain't no cure for the summertime blues

Eddie Cochran, 1958

On April 17, 1961, in the early morning, would begin what has become known in history as the Bay of Pigs: a full-scale invasion of Cuba by 1,400 American-trained Cubans. However, the invasion did not go well: The invaders were badly outnumbered, and they surrendered after less than 24 hours of fighting. Just a year earlier, on the same day, but on a cold English morning, Eddie Cochran died in a car accident in Chippenham, two years before Summertime Blues entered the Billboard charts. The history of music, like the history of revolutions, is written from myth, error, failure and enthusiasm. When Eddie Cochran died, the taxi and other items from the crash were impounded by local police waiting for a coroner's inquest to be held. David Harman, a police cadet at the station, who would later become known as Dave Dee of the band Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich, taught himself to play guitar on Cochran's impounded Gretsch. Dave Dee's band found success in 1968 with their hit song Legend of Xanadu.

When Fidel Castro backed the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1968, an accelerated process of abandonment of the ideals of the New Left began in Cuba. 1968, as Todd Gitlin recently recalled in The New York Review of Books, was also "the year of the counterrevolution", of the Soviet tanks in Czechoslovakia, of the Tlatelolco massacre and of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. In that summer, in Havana, as in Prague or Memphis, the counterrevolutionaries won.

However, perhaps it was Joe Strummer, a philosopher best known as the leader of the band The Clash, who said that 1968 had, definitely, been a great year to come of age. The world was about to end: Paris, Vietnam, the hippies and a countercultural universe was exploding like an erupting volcano. He claimed that all that opened the doors of punk for him, however, by that year others had already found the doors of perception open.

Between the influence of southern music and psychedelia, 1968 was a great year for rock: A Saucerful of Secrets, Pink Floyd's iconic album for marking the departure of Syd Barrett and the arrival of David Gilmore, Velvet Underground and their first album without Nico, Hendrix known as the star that fell from the sky and left Clapton and Pete Townshead, guitarist of The Who, without a job. The Stones revealed their sympathy for the devil. Robert Wyatt gave experimental Jazz to psychedelic rock by releasing the first volume of Soft Machine, Jim Morrison and his Doors had opened a whole labyrinth to go through and The Beatles with a White Album that is not as white as it claims to be, as some of its lyrics could be a suicide manual, were once again revolutionizing pop music.

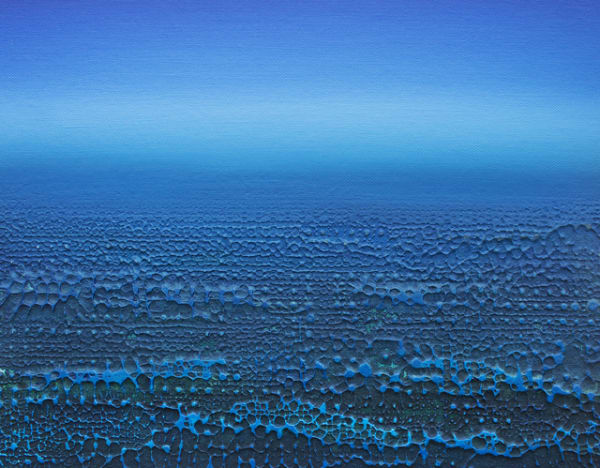

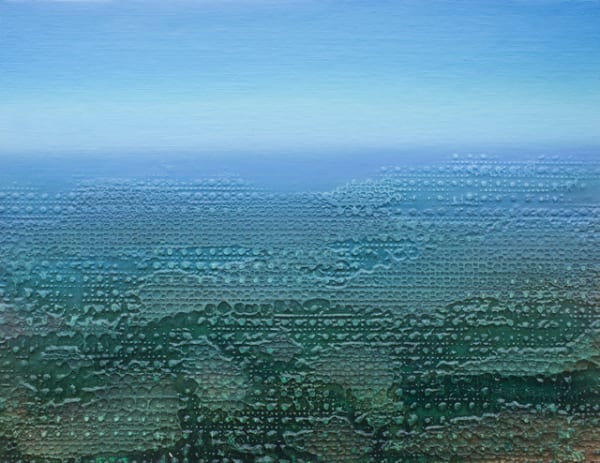

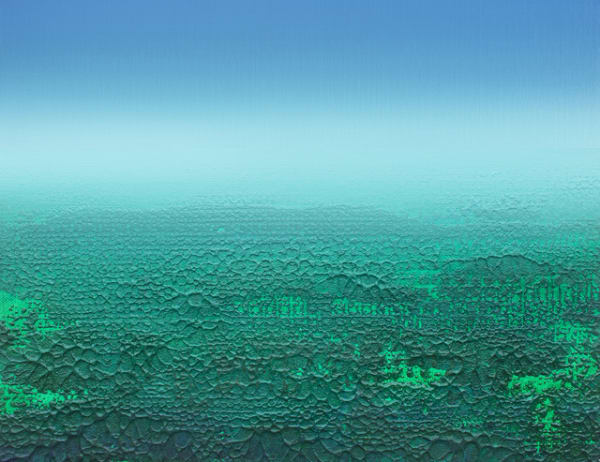

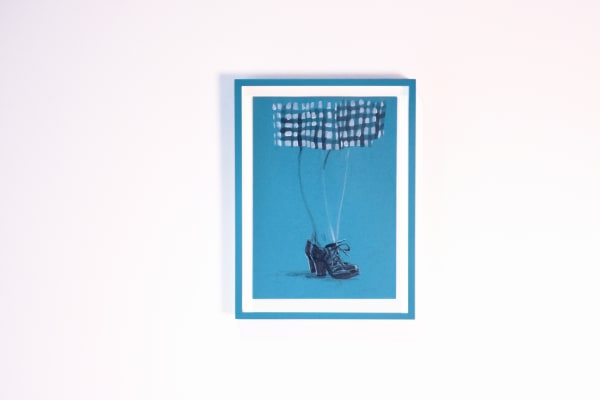

At the end of that year, on December 26th, Led Zeppelin make their American debut. In the press it would remain: The concert was cranked off by another heavy, the Led Zeppelin, a British group making its first U.S. tour. Blues oriented (although not a blues band), hyped electric, the full routine in mainstream rock – done powerfully, gutsily, unified-ly, inventively and swingingly by the end of their set. That same day, but several centuries earlier, in 1714, the Virgin of Regla was declared patron saint of Havana. There it would remain, for centuries to come, its color and its presence as an emblem of the Caribbean capital. A necessary trip if you want to cross the seas. Saint and Orisha, it is not surprising that Havana is then a blue city, demarcated by water, faith, the malecón, baseball, the colonial blue doors painted by anonymous hands, that survive centuries of neglect and oblivion, and the blue desire to leave and stay. A Black Virgin, for a town of colors, guarding a bay of frustrations. Summertime Blues could perfectly be the soundtrack of a Havana afternoon: The inordinate fatigue, the adolescent sense of injustice, the revoked car privileges, the heaviness of a blues guitar in a dark and lawless south.

In 1977, NASA launches, into space, as a representation (and explanation) of life on earth, Voyager 2, with 27 song samples. Among them is Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground, written and performed by Blind Willie Johnson, blinded when he was 7 years old by his stepmother; (who threw lye in his face in retaliation for Johnson's father's infidelities). Science writer Timothy Ferris, who selected the songs, explained: "Johnson's song concerns a situation he faced many times: nightfall with no place to sleep. Since humans appeared on Earth, the shroud of night has yet to fall without touching a man or woman in the same plight.”

It should be added that since Blind Willie Johnson was actually blind, perhaps the idea of darkness was lost in his memory as a blind child, but not the idea of the color blue. In 1923, Clyde Keeler, an American geneticist, discovered that even blind people, all of us, possess a special receptor that always reacts to blue light. Perhaps a paradox between history, science and art, there are theories that suggest that before humans had words for the color blue, they actually saw the sky in another color.

Maybe the blind can see the blue, maybe if one day we don't hear, we can still hear the blues. When Roger Waters wrote Set the Controls to the Heart of the Sun, one of the most psychedelic and beautiful tracks on the '68 album, A Saucerful of Secrets, he did so with an anthology of Tang Poetry in his hand. So, one of the verses of the song that evokes a lonely man and his wine on a mountain, presents before the rock of the sixties, Li Po, the banished immortal, an ancient Chinese poet who drowned drunk in a river trying to reach the moon through his reflection. It is curious that the following year mankind reached the moon.

Ain't No Cure, a group show, full of blue, at Thomas Nickles Project.